The House That Abe Built

June 13, 2022

In a capital of great public buildings, the private Washington is often forgotten, or at the very least, overlooked. Rare is the civic asset that was not a grand federal project or a monument to a favorite son.

"About 50 years from now, when they ride by here, people will ask, who built that building?" said Abe Pollin to the Washington Post in 2001. "Some guy named Smith, they'll say. Because no one remembers."

But they should. This year, the building now known as Capital One Arena celebrates its 25th anniversary as a cornerstone of the Nation's Capital, as well as an integral part of the Georgetown University basketball experience. That is exists at all is a monument to a man who would not take no for an answer, and in so doing, changed the course of the city itself.

By its own admission, Washington D.C. is not a sports town, and its legacy reflected it. No great college stadium or arena was ever built in Washington. Griffith Stadium was never confused for Yankee Stadium, and is among the least remembered of baseball's golden age of ballparks. Uline Arena, once its largest indoor facility, sat abandoned for nearly two decades.

By late 1971, just one professional team remained in the District, and the Washington Redskins lost more than a little of its soul when it packed up for a parking lot in Maryland two decades later. It was in this era that an ambitious construction owner set sights on bringing not one, but two professional teams to Washington--it just took a little longer than he would have liked.

Abe Pollin was not sports royalty. Raised in Washington, educated at George Washington, and living in Bethesda, Pollin built multi-family construction projects in the Washington area and took an interest in an NBA team which had recently moved to Baltimore from Chicago. Few cared about the Chicago Zephyrs, but its new name, the Baltimore Bullets, drew his attention.

In 1964, Pollin called Bullets owner Dave Trager with an offer to buy the club, a expansion team Trager had purchased for $200,000 three years earlier. Having never heard of him before among the names of contemporary sports executives, Trager thought he was nuts. Pollin asked for a meeting that day, flew straight to Chicago, and bought the Bullets for a record $1.1 million with two other investors, whom he bought out four years later.

After eight mostly successful seasons at the Baltimore Civic Center, Pollin saw an opportunity to build a home closer to Washington. District of Columbia officials agreed and sought $15 million in public funds for a new arena for the Bullets but could never quite decide on a location, which varied between a plot of land at Mount Vernon Square and less desirable locations along the railroad tracks at Florida Avenue and New York Avenue NE. District funds were tied up with Congressional appropriations, which became further tangled with promises of combining an arena with a convention center to be built for the nation's bicentennial in 1976.

Either way, Pollin was running out of time. In the summer of 1972, Pollin had been awarded an NHL expansion franchise to go along with the Bullets, but without an arena by the fall of 1973 it would be awarded to a group in Cleveland. He couldn't wait until 1976, nor would he.

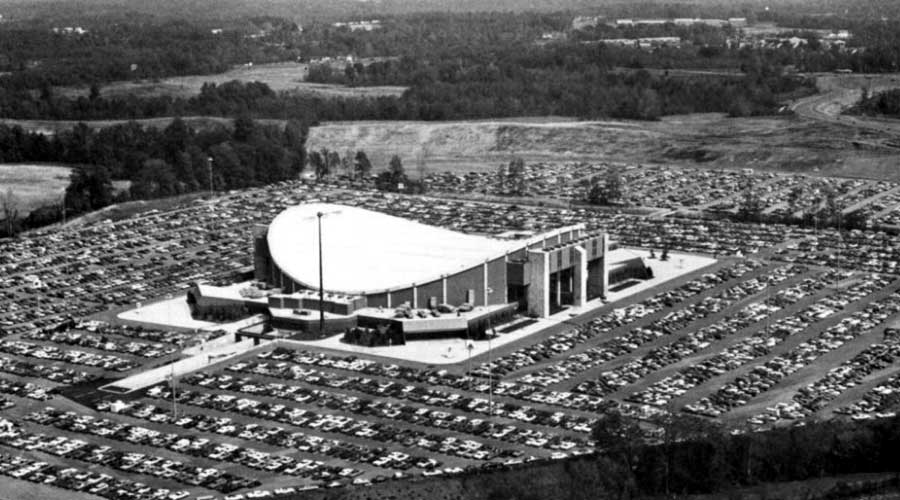

"I will stand by my word" to build in Washington if the city came through, Pollin insisted, but he was actively pursuing other options: a new arena in Baltimore at Camden Station was proposed, another in Columbia, MD. That spring, officials in Prince George's County offered a 50 acre tract in a wooded area abandoned during the construction of the Capital Beltway. Congressman Larry Hogan (C'49, L'54), a Georgetown alumnus and the father of the current governor of Maryland, helped broker a deal with Pollin and Prince George's County for a forty year lease for the land, plus a share of gate receipts. In August 1972, Pollin chose the site outside Largo, later assigned to the unincorporated area of Landover, and went to work on a rapid construction schedule. Fifteen months and $16 million later, Capital Centre opened on Dec. 2, 1973.

By the standards of the 1970s, the arena was revolutionary: a futuristic design that placed the majority of of its 19,035 seats facing mid-court. It was the first arena with a video board, known as "Telscreen" hanging above the floor. It was the first arena with twenty sky boxes at each end of the building for corporate guests, and featured an exclusive private club off the main concourse. While some amenities never quite came to fruition (including the promise of hundreds of locust trees to provide shade in the arena's vast parking lots), Capital Centre was soon hosting 200 events a year, and in 1981, welcomed Georgetown University basketball, the Hoyas having outgrown its 4,000 seat gymnasium on campus and lacking any good options to meet the growing interest. The arena stood almost 45 minutes from the campus.

"I didn't particularly want to go to Cap Centre, but I feel we don't have a choice," said coach John Thompson. "I would have preferred an on-campus arena, but I'm not the one in the President's chair. I am afforded that limited view because I'm just a coach, but he has to look at the larger view."

Accessible only by car, with no restaurants, hotels, or other retail within three miles of the complex, it was no less a destination for sports, for concerts, even a presidential inaugural parade in 1985 when conditions were too cold in the city. Capital Centre was the hub of major events in Washington for the next two decades, even as the city's downtown was crumbling. The arena returned millions in tax revenues to the Prince George's County budget.

And that convention center in downtown Washington? Planned to open for the Bicentennial, it opened seven years late, millions over budget, and never broke even. Functionally obsolete at the start, it was not designed for sports or entertainment events, and closed in 1998.

Over the intervening years, Capital Centre had not aged well. Distant and disconnected from the Washington community, the innovations of the 1970s paled in comparison to the newer arenas debuting around the nation. It did not go unnoticed in an era of luxury boxes and premium amenities, Pollin had not made any upgrades to the building. The new stars of the NBA and NHL game arrived with big contracts, something that Pollin's personal finances had struggled to compete with.

By 1993 it was apparent that Pollin would consider offers to replace Capital Centre. Various sites for a new arena were offered in casual and not so casual discussions. Some suggested moving back to Baltimore, with a complex adjacent to the new ballpark at Camden Yards. Virginia officials proposed $100 million to build an arena south of Springfield in the Fort Belvoir area, but it could not secure funding to extend a rail line six miles to the arena site.

Having failed to land a deal with the District and a subsequent plan in Northern Virginia, Washington Redskins owner Jack Kent Cooke proposed a "Meadowlands South" at Laurel Race Course to include facilities for the Redskins, Bullets, and Capitals at the complex. An attempt to get Maryland legislators to renovate the Landover site was dismissed in Annapolis, as legislators supported the ill-fated Laurel plan, which was halted by community pushback.

Washington civic leaders saw an opportunity. Six months earlier, at a board of directors meeting of the Kellogg Corporation, Washington civic leader Ann Dore McLaughlin had a conversation with Gordon Gund, owner of the NBA's Cleveland Cavaliers. It was Gund, a longtime friend of Pollin, who was in the process of moving the Cavaliers from a distant suburban arena, the Richfield Coliseum, to downtown Cleveland as part of a revitalization effort. Gund told McLaughlin he thought Pollin might take interest in such a project in Washington.

What became known as the "Cleveland model" quickly took root among local leaders, and Washington had its first exploratory meetings with Pollin followed, focusing on forming a public-private partnership for an arena in the Gallery Place neighborhood.

Once a residential area that stood between the city's Chinatown and commercial districts, Gallery Place had fallen into disrepair by the 1960s. A local financial group with ties to Mayor Marion Barry, Capital Landmark Associates, was awarded a development deal in the 1980s, putting up just $850,000 for property rights which would later be assessed for as much as $90 million. Various proposals, ranging from movie theaters to low income housing to a 13 story hotel, all fell through. The deal was cancelled outright by Barry's successor, Sharon Pratt Kelly, but the land still stood vacant.

The redevelopment opportunity was not lost on Pollin, who saw the confluence of three Metro rail lines as a singular opportunity to do what Landover could not: enable public transit to transform the facility, and the city which surrounded it.

"It could be one of the major buildings downtown," he told the Washington Post. "Metro exits would come out of the building, like Madison Square Garden. It's a fabulous possibility that intrigued me. People have told me, 'Build it, Abe, and we'll walk there in five minutes or take the Metro there. You'll sell out every game.'"

In late 1993 the District government announced a plan to appropriate $90 million in public funds towards a $180 million downtown arena on the Gallery Place footprint. Maryland officials were openly dismissive, questioning how Pollin would address outstanding payments still due on Capital Centre and whether the cash-strapped District would come up with its share of the costs.

"They don't have two nickels to rub together down there," said state senator Arthur Dorman.

Much of 1994 was an extended delay for the project. Commitments for public funding were never finalized. A federal audit found the District faced a $500 million budget deficit by the end of 1995 and calls grew in Congress to take over the District's finances. Mayor Kelly, who failed to secure a stadium deal for the Redskins just two years earlier, seemed to be going down a similar road with Pollin.

That summer, Kelly was repudiated by voters in the 1994 Democratic primary, where she received just 13 percent of the vote. Few predicted the outcome of the primary when former mayor Marion Barry, having been run out of office after a drug possession charge four years earlier, was selected as the presumptive mayor-elect. The election effectively tabled the decision on arena funding until the second Barry administration took office, an administration that was expected to fall under Congressional financial oversight.

Further complicating matters was a competitor. Robert Johnson, CEO of the Black Entertainment Television network, announced he would privately finance a 24,500 seat arena on land he owned in what is now the NoMa neighborhood, with an expectation he would be offered ownership in the Bullets, and suggested that he would pursue a NBA team of his own for the arena if Pollin refused to sell. (The NBA quickly quashed any talk of adding a second team to Washington.) By November, Johnson dropped the offer to build his own arena, but announced he would personally cover the District's $90 million investment to gain an equity interest. Pollin was not looking to sell to Johnson under either circumstance, but the funding intransigence had stalled any momentum for the downtown project, which remained under District control.

With all this going on, it would have surprised few if the 71 year old Pollin would have just washed his hands of the District a second time, negotiated a deal with Prince George's County, or simply cashed out. Pollin had recently turned down a $170 million offer to sell the teams and the arena to Roland Betts, a New York financier and part owner of the Texas Rangers, but Pollin understood that the principle of diminishing returns on the existing arena was affecting the long term value of the franchises.

The story took an abrupt turn on December 28, 1994.

Pollin held a news conference to announce that he would build the arena at Gallery Place, borrowing the entire amount needed for construction.

Further delays "would be long and arduous," Pollin stated. "I decided to take a risk. I have no idea where the money's coming from right now, but I'll get it somewhere, somehow."

The eventual amount ($260 million) was a staggering sum for a man reported to be worth just $50 million. He leveraged everything he had, and went to work on the rest. The sports franchises were valued at $125 million. He convinced MCI Corporation to commit $44 million on a 13 year naming rights deal, a huge increase from the $1 million being paid by US Airways, who had just bought the naming rights to Capital Centre earlier that year. The 40 skyboxes in Capital Centre grew to 110 in the new arena design. Pollin promised 4,000 club seats, 20 percent of the capacity of new building, at premium prices, as a means of building revenues to meet debt service.

"I've got everything I've ever done in my life on the line," he said. "I've pledged everything. My advisers think I'm nuts. But I wanted to do something special for my town."

On Dec. 2, 1997, the 24th anniversary of the original opening of Capital Centre, the new MCI Center debuted to universal acclaim. The final cost was 16 times what he spent on Capital Centre and one of the largest construction projects in Washington history at the time. Pollin passed on architectural touches to focus on getting the building done under budget; thus, initial plans for sweeping views of the Capitol and rooftop restaurants fell victim to cost control. But at its opening, no one seemed to mind.

As Pollin predicted, thousands of fans used Metro that first evening, a five-fold increase of traffic at the station. (Pollin said he rode the Metro from Bethesda that morning, just to see what it would be like.) The few restaurants that existed in the neighborhood were quickly sold out, as fans arrived early to see everything up close. A sports marketing executive told columnist Michael Wilbon of the Washington Post that "you don't understand. There are no words for this."

"Do you know what this means to Washington?"

That evening, before a sold out crowd of 20,674 that included President Bill Clinton, the recently renamed Washington Wizards defeated the Seattle Supersonics 95-78. As the front page of the Post proclaimed, "Last night, downtown Washington was a place to be, not to flee."

Opening night was an unqualified success. The second night belonged to Georgetown, with mixed results.

After its first three home games of the season in Landover, averaging 6,000 per game, the Hoyas opened MCI Center on December 3, 1997 before 13,181 in attendance, its largest crowd in almost two seasons. The Hoyas fell to Villanova, 73-69, shooting just 8 for 22 from the foul line.

"I don't think we were very focused," said senior captain Boubacar Aw after the game. "The fact that we moved to the MCI Center was one of the reasons."

Georgetown's meteoric rise in college basketball over the prior two decades had gone hand in hand with Capital Centre, where it was 199-30 (.868) since 1981. Capital Centre was often too big for Georgetown, as the Hoyas sold out that building just 17 times in 17 seasons. At 20,500 seats, MCI Center (and the names that would follow it) was too big as well, but with a significant increase in amenities and the opportunity to afford its students easier access to the games.

There were some early concerns centered around the Georgetown fan base, particularly those in Montgomery and Prince George's counties, who might have preferred the easy access along the Capital Beltway as opposed to driving downtown and finding suitable parking. In the end, the concerns proved unfounded. In its first five seasons at MCI Center, Georgetown sold over 700,000 tickets during a period where GU qualified for just one NCAA tournament appearance.

Georgetown's first sellout at the arena came did not come until January 2004 to #1-ranked Duke, who went on a 27-5 run at the end of the first half en route to a comfortable 85-66 win. Two years later, Duke was again #1, and returned to a sold out arena. An 87-84 Georgetown upset on national TV was its biggest win in a decade, with students spilling onto the floor at game's end, something never seen in Landover.

"This was not an outcome unduly affected by from fouls, from injuries, or an improbable shot at the buzzer," wrote the HoyaSaxa.com recap that day. "For forty minutes, Georgetown's patience and precision was stunning in its effect on the nation's #1 team, which entered the game with a 106-5 record against unranked non-conference opponents."

"Just what a superb performance," said Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski in post-game comments. "They were so deserving. If you get beat, you want to get beat by people who earn it, and they earned it."

In 2010, Duke made a third and final visit to see the Hoyas. Before a sellout crowd which included President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden sitting courtside, the Hoyas led by as many as 23 points in the second half en route to an 89-77 win, shooting 71 percent from the field. The Washington Post called it "a game in which the building shook, the leader of the free world applauded, and Georgetown won going away."

From 2006 through 2013, Georgetown reestablished itself in the national basketball discussion, with MCI Center at the forefront. During these seven years, the Hoyas posted a 98-17 (.852) record in the building, including 28 straight from 2007 through 2009. Of its 115 games downtown, Georgetown was nationally ranked in 90 of them.

One of its most memorable games for Georgetown fans came on March 6, 2013, the final regular season game of the season against Syracuse, who was departing the Big East conference after the end of the season. Georgetown set an arena record with 20,972 in the building, routing the Orangemen 61-39 for the regular season title and holding Syracuse to its fewest points in any game since 1962.

"It's special because the Big East, as we have known it, is ending," said coach John Thompson III. "Georgetown won the first one, and now Georgetown's won the last. So that means a lot."

The arena, then renamed for MCI's successor company, Verizon Communications and later retitled as Capital One Arena in 2018, had firmly established itself as the home of the Hoyas.

After a quarter century, it goes without saying that Capital One Arena is an integral part of Georgetown basketball. While playing in an NBA arena is no longer the novelty it once was to college athletes, this remains an elite facility for hosting college games. When it's sold out, it's a great environment. When a game is played before 16,000 empty seats, it can be more a little deflating, too. Decades of institutional indifference to invest in an on-campus or a near-campus arena option has provided today's University no meaningful choice other than Capital One Arena and with it, three decades of students and alumni who know no different. The last undergraduate class at Georgetown to experience a full season of on-campus basketball turns 60 this year.

Georgetown never discloses the cost it pays for renting the facility, as Capital One Arena is among the most expensive arenas in the nation and one of the largest expenses across the entire Georgetown athletic budget. To play Big East basketball, it's the only game in town, and Georgetown has no choice to pay the price. But if the alternative was playing games in Landover, in Laurel, or even Woodbridge, rest assured that Georgetown would be happiest paying rent where it is now. As its own downtown campus grows in the coming years, Capital One Arena may be even more aligned to the Georgetown of the future.

A quarter century later, the arena has changed Washington in ways that were entirely expected, and some that were decidedly unexpected.

At the outset, Abe Pollin predicted as many as half of arena visitors would arrive by public transit, and his prediction was remarkably accurate. On any evening, approximately 11,000 attendees exit Gallery Place according to Metro statistics, making this stop the third busiest in the entire rail system, trailing only Union Station and Metro Center.

As it was designed, Capital One Arena did not have underground access to Metro, meaning visitors must walk outside for a block or so before entering the arena. With this, fans immediately began to search for a bar, a restaurant, or some place to visit before and after the game, and businesses took notice. Restaurants began to spring up in the area immediately adjacent to the arena, and soon began to expand into the adjacent blocks, including those areas in Chinatown and in blocks west and north of the arena.

Within six years, the neighborhood (known by its regional title of Penn Quarter) opened more restaurants and bars per square mile than anywhere in the District, displacing Georgetown, the previous center of D.C. nightlife. And it wasn't just fast food--soon, some of the city's finer dining options wanted to be where the people were, which in this case, was within walking distance of the arena.

Commercial development followed. As new office buildings returned downtown, the promise of pedestrian activity and reliable public transit added to its market value, as well as underground parking, which could be monetized in off hours for those driving into the city for events. Upscale hotels, once relegated out of downtown for fear of crime, began to be built along a corridor from 12th Street east to 5th Street. Pedestrian traffic along F Street, once the city's commercial hub, returned with a flourish.

Three blocks from the arena stood the grounds of the former convention center, having been razed years earlier. Construction began in 2011 on the largest downtown project in the nation: City Center DC, a $850 million development transforming 10 acres of parking lots into offices, restaurants, hotels, housing, and a lineup of high-end retail storefronts that rivaled Fifth Avenue in New York. What was once an abandoned part of downtown now welcomed storefronts of Tesla, Tiffany, and Giorgio Armani, with apartment rents beginning at $2,900 to as much as $10,000 per month.

Would this development have come independent of Capital One Arena? It's not altogether certain, but the spark engendered by pedestrian traffic and nightlife around the arena provided the momentum to the city to reimagine and reshape parts of the city it had neglected for decades. What is certain is the tremendous changes in downtown Washington over the last 25 years have placed Capital One Arena at the confluence of change in the social and cultural identity of the city, centering on the transit corridor known as the Green Line.

When Metro was designed in the early 1960s, the Green Line was not in the original plan, as inner city Washington was not considered a site for commuters. (The early focus on commuter rail is cited as the reason a stop was not planned for Georgetown.) Congressional delegate Walter Fauntroy successfully lobbied Congress to include a rail line through some of the poorest neighborhoods of Washington to gain transit access offered elsewhere in the city, but the line was beset by construction delays and didn't open until 1991, 15 years after Metro had opened in the rest of the city.

One of the Green Line's two major transfer points, Gallery Place stands in the middle of an economic development region from the Petworth neighborhood on the north, to the Navy Yard on the south. According to a 2017 study commissioned by the Capitol Riverfront Business Improvement District, the growth in this area has been remarkable:

- One of every two new households in Washington under the age of 35 are now living adjacent to the Green Line.

- One of every four new apartments in Washington are now built along the Green Line.

- The average income for households along the Green Line have increased 50 percent since 2012.

- Half of all new retail development in Washington is along the Green Line.

South along the Green Line are industrial sectors of the city which are also being transformed--the areas around Nationals Park and Audi Field, for example, as well as a $2 billion upgrade of the Southwest Waterfront. As with Penn Quarter, upscale restaurants and luxury hotels are fast followers.

The changes are more than economic. Today's residents along the Green Line are younger, higher income, and white, a contrast to the working class African-American residents who lived in these neighborhoods since World War II. The popularity of living along the Green Line has also accelerated redevelopment in adjacent neighborhoods such as Logan Circle, Ledroit Park, and Shaw, a visible change to a city that once identified itself as "Chocolate City". Amidst the changing black population of Washington (from 70 percent in 1980 to just over 44 percent in 2022) the fault lines between redevelopment and gentrification have been opened, as much of the generational change of the city can be seen along this corridor.

"These new condos invite a new demographic," said Nizam Ali, co-owner of Ben's Chili Bowl to the Howard University student newspaper. "Our regulars have either moved or passed away."

And then there is Georgetown basketball. Average home attendance has dropped by over 50 percent since 2012. Much of that is a trend of the losing ways of the last eight years, but it's not the only factor. The fastest growing segment of the population, the residents of the Green Line, never grew up with John Thompson or Patrick Ewing in the sports pages, or are fans whose college interests are elsewhere.

What interest, much less loyalty, does "New D.C." have for the Hoyas, even when games are mere minutes from their home on Metro? Do they care?

At the time of his death in 2009, Abe Pollin had been an NBA owner for 46 seasons, the longest tenure of any owner in the league. "In the changing world of professional sports, Pollin stood out for decades as an owner who tried to run his teams like a family business," wrote the Associated Press. "He bemoaned the runaway salaries of free agency and said it would have been difficult for him to keep the Wizards if it weren't for the NBA's salary cap."

Pollin's two sons did not want to take over the business, and seeing what happened to the Redskins after Jack Kent Cooke's death, he decided to act. In 2000, Pollin sold the Capitals and a 44 percent interest in the Wizards and MCI Center to Ted Leonsis (C'77), a Georgetown alumnus and former executive at AOL, for $200 million. After a protracted negotiation following Pollin's death, Leonsis purchased the remaining 56 percent from the estate for $550 million. The house (and teams) Abe built now reside under the ownership of Monumental Sports & Entertainment, a $3 billion enterprise based at Capital One Arena.

Contrary to some that assume Leonsis owns the entire company, he does not. (According to the Washington Business Journal, philanthropist Laurene Jobs is the company's largest shareholder.) While Monumental engages in a number of enterprises from health tech to e-sports to streaming media, the majority of its revenues still flow through the building at 6th and F Street.

What is its long term future?

In 2018, Leonsis committed $110 million to an upgrade of Capital One Arena, which was mostly in seating, video, and concessions, but did not address long term infrastructure. At the time, Leonsis said he would like to get "20 more years" out of the building, in an era where many sports facilities become obsolete within 25 to 30 years. Excepting Madison Square Garden, which was gutted and renovated between 2011-2013, the oldest active NBA arena was built in 1990. At present, Capital One Arena is the 10th oldest facility in the NBA and 15th oldest in the NHL.

The cost of new arenas are increasingly prohibitive, even for Leonsis. The Chase Center, the downtown home of the Golden State Warriors, cost $1.4 billion to open in 2020. The Intuit Dome, now under construction for the Los Angeles Clippers, will cost $2 billion. And while Monumental would have no shortage of suitors in Virginia and Maryland willing to fund portions of a new arena if the teams were to move out of downtown, none have the location and the economic engine that has served it so well. Other than Madison Square Garden, no arena is as strategically located within a city.

""Do you know what this means to Washington?" was the question asked that evening in 1997. We didn't know then, but we know now.